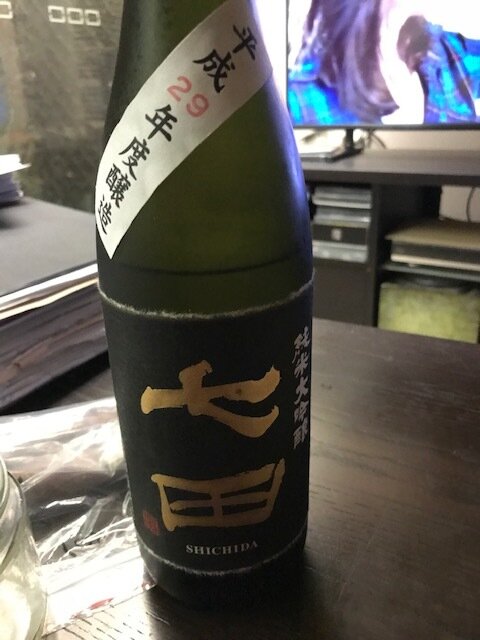

Bolivar Belicosos Finos – Shichida Junmai Daiginjo Sake

Interesting combo this week. A popular and well-known cigar with something a little more left field – a cracking sake.

The Belicosos. A pyramid, 52x140mm. A cigar which, according to Trev’s magnificent site, has been with us since pre-1960.

This example smoked very well. rich, chocolatey, dark fruits. It took a little time to get into stride but went well when it did. It was more Christmas cake than the typical earthiness one thinks of when one smokes Bolivar. This smoke had what seems to be referred to as ‘the elusive perfect draw” but what is that? Over to Ray, I think? Slightly tight is pretty close for me. And this was.

Overall, a long slow smoke. Always like that. Quite powerful as would be expected. The construction, slightly ragged but it worked. A forceful cigar.

The finish saw a lot of pepper emerge. This Beli was a fine example and a cigar I enjoyed. For me, 92.

And it worked amazingly well with the sake. That lovely umami character of a good sake is something that does well with a good cigar. This is a combo which needs a lot more exploration.

Sake. If I may, as I have done before, plagiarise myself from part of a piece I did for Quill and Pad, to most Westerners, it a drink shrouded in mystery. Rice wine? Japanese spirits? All the same thing? Must be drunk warm? Myths abound.

If you were like me, your first exposure to sake was possibly in the 007 thriller, ‘You Only Live Twice’, when Bond first meets his Japanese counterpart, ‘Tiger’ Tanaka. Offered a martini (I still maintain a martini must be from gin, not vodka), he opts for sake, “especially when it’s served at the correct temperature, 98.4 degrees Fahrenheit, like this is”, impressing his host.

A more practical exposure soon came as students trying a local Japanese restaurant. Sake was compulsory, even if we knew nothing about it. But it was warm and alcoholic – what more did a student need?

Looking back at our friend from MI6, interesting palate if he can tell temperature down to the decimal point, but it was not long before we were being told that drinking sake warm was very poor form. Could 007 have got it wrong? And I am still not certain many of us had a clue as to what it was.

Sake is made from rice. Fermented rice, although the process that sees the conversion of starch to sugar has more in common with beer than wine or spirits. It has been part of Japanese life for more than 2,000 years. Some believe it actually dates back to China around 4,000 BC. Its importance to Japan can be seen if one goes back to the early part of last century, to the

Russo-Japanese War. Homebrewing of sake was banned as homebrewing meant tax-free and the taxes on sake, at the time, made for an extraordinary 30% of all revenue the government was collecting. It is still forbidden, although sake only makes up 2% of government revenue these days.

Simple the process might be, but there are all manner of versions, levels of quality and brewers (they are referred to as brewers, not distillers). There are some 2,000 sake breweries littered throughout Japan, so it takes little imagination to see that there must be an incredible number of very different sakes on offer.

Basically, sake is rice, water and the fermenting agent called koji. The result is an alcoholic level that usually sits between 13 and 16%. The rice used is different from the standard table rice so popular with Japanese food. Rather, it is the soft, low protein, large-grain varieties. More than 80 varieties are suitable for sake. Needless to say, the water is also important. Different brewers will claim their particular water is superior – similarities to the production of whisky are common.

Koji is not strictly a yeast but rather cooked rice/soya beans inoculated with a fermentation culture. It is also used for mirin, miso, rice vinegar and soy sauce. For the production of sake, it reduces the carbohydrates in the rice into sugars, which subsequently ferment (as per wine) resulting in alcohol and carbon dioxide. Koji is also vital in that it contributes to the umami character, crucial to good sake. Few drinks anywhere in the world are as rich in the umami character as sake, thanks to a much higher percentage of the relevant amino acids. Worth noting that the more polished the rice, the less of the umami character that gets through.

Good sake should be consumed within a week of opening the bottle – and kept refrigerated – although a day or two is far better. Sake should usually be consumed within a year of production. For serious appreciation, the tiny glasses often used are best avoided. The theory was that very small glasses led to the host continuously refilling his guests’ glasses, promoting hospitality. A guest should never be left to fill his own glass.

180 is a key figure in sake appreciation. The standard bottle is 720 ml, which is four times 180. Big bottles are 1.8 litres, which is 180 by ten. Although sake is very often used for toasts in Japan – ‘kampai’ is Japanese for ‘cheers’ – to appreciate good sake, it should be sipped, not treated as a shooter and slammed down. For those for whom these things are important, sake is gluten-free and contains no preservatives. It is an ideal drink for many foods – that umami character makes it a perfect match for foods similarly blessed. Think seafood, meats, mushrooms, aged cheeses and more. Lots of fun to experiment.

This leads nicely to the types of sake that are available. The five main types are Junmai-shu, Ginjo-shu, Daiginjo-shu, Honjozo-shu and Namazake, but there is more. The polishing/milling of the rice is key – the degree of the polishing is referred to as Seimai Buai. The milling removes the bran and hence the protein and oil contained in the grain.

Junmai-shu. This is an ‘unadulterated’ sake with no alcohol added. The Seimai Buai is a minimum of 70%, meaning that no more than 70% of the rice maintains its original size (hence, 30% of the grains have their outer layers removed – so a sake with a rating of say, 60% will have had 40% of the grain removed. Rice for consumption will be polished to 90% or more, meaning only 10% or less of the grain is removed). These are not actual legal specifications, but must be mentioned on the label. These sakes range from mellow to fuller and richer styles. The acid levels tend to the higher end of the spectrum and brewer’s alcohol is not added. This is a style often served hot. Sake which has had a higher percentage of the rice grain removed will naturally be more expensive, though not always better.

Ginjo-shu. Here, 40% milled, hence 60% at original size. This is an aromatic style of sake and tends to the more elegant, delicate and lighter. Usually served cold. Alcohol may be included. Fermentation takes place at a lower temperature.

Daiginjo-shu. A type of Ginjo-shu sake, where the milling is just 35% to 50%. Again, the aroma is key. These are fuller styles while retaining a delicacy.

Honjozo-shu. Sake which also has 70% milling but includes the addition of brewer’s alcohol. This is considered to give a lighter body and smooth taste. Often served warm.

Namazake. Any type of sake can be Namazake. It is where the sake is not heated for pasteurisation after the final mash is pressed. Should be kept chilled.

Jizake is sake produced by small brewers.

Unfiltered (or lightly filtered) sake is called Nigori-zake. The process (or lack of it) results in a cloudy product and often has some koji rice left in the bottle. Usually sweet. Kijoshu, which uses less water and more sake during the fermentation process, is also considered to be ‘dessert’ sake.

Koshu is sake which has been aged for a longer period than the usual 9 to 12 months, giving it a more powerful texture and flavour.

Sake aged in wooden casks is Taruzake.

Sake is usually diluted by the addition of water before bottling, giving an alcohol level around 13 or 17%. If it is not and has a level around 17 to 20%, then it is referred to as Genshu.

Akai sake will have a reddish hue, resulting from a specific type of koji.

Sake can be infused by various fruit flavours, making it ideal for cocktails. There are also sparkling versions, which are created by a secondary fermentation and usually have a lower level of alcohol. You can even find sake with gold flakes in it, called Kinapaku-iri. Needless to say, it is not cheap. Arabashiri is sake that has not been matured, produced from the first sake out of the press of the rice mash.

Until a couple of decades ago, there was an official ranking system for sake but this is no longer in existence.

The water used for brewing sake is called Shikomimizu. Needless to say, it varies greatly, from hard to soft, depending on the brewer. Hard water, that with a high mineral content, gives a powerful profile to the sake while the softer waters produce a more gentle result and give a sweeter impression. The aromatic profile is usually considered to be as a result of the different yeasts used. Originally, the local yeasts were used but, as in the case of wine, with the development of various commercial cultures, it is possible for a brewer to source a yeast to give the result they seek.

The conventional wisdom which had everyone drinking their sake warm is said to have come from a time after WWII when rice shortages forced brewers to fortify their sake with distilled alcohol. Warming it helped knock the edges of any imbalance or sharpness. By the late 60s, breweries moved to ‘pure rice’ sake, with no distilled alcohol involved. The higher quality allowed consumers to drink their sake chilled. Heating sake now is done where the flavour profile benefits. Similarly, the addition of alcohol during production is now a stylistic choice. The term for warm sake is Kanzake. It can range from room temperature, around 20°C, to very hot, at nearly 60°C.

The Shichida Junmai Daiginjo (A$113) is from the Saga Prefecture in the Kyushu region. The brewery, known as the Tenzen Brewery, dates back to 1875 when the Shichida family bought some equipment to assist a local who had gone bankrupt and remained involved. This sake (16%, 45% milling) is made from Yamadanishiki rice. The family is currently 6th generation. The water is medium hard and the region’s warmer temperatures help to make a clean, delicate style, yet full-flavoured and well-structured, with noticeable umami character.

What is immediately apparent here is the floral aromas which fill the glass. Enticingly fragrant with stonefruit flavours. If you want to know just what the character of umami is, try this sake. Underlying power and impressive length. Gorgeous, supple texture. This would be ideal for lighter dishes and yet has the intensity to carry something spicier. There is a certain hedonistic note to this sake. Delicious.

If you are not familiar with top sake, now is the time. And a good cigar with it, even better.

KBG