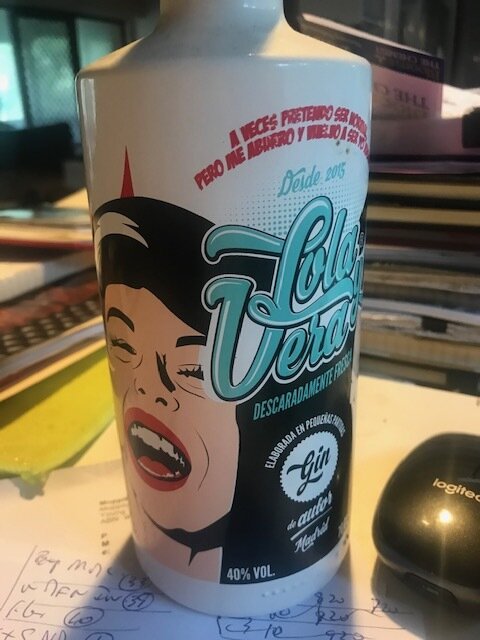

Trinidad Coloniales – Lola y Vera Gin.

The Santamania ‘Lola y Vera’ Gin comes in a bottle which looks a bit like a cross between a bottle of kids’ medicine and a bottle of Malibu on acid. It was released a few years ago as a collaboration between the Spanish distillery, Santamania, and our own Four Pillars, though the latter rarely appears in any info on it. Spain is a huge consumer of gin and they do it extremely well.

‘Lola y Vera’ is a fine example. Named after their stills, it is described as a Madrid Dry, based on the juniper-flavoured London Dry with which most are more familiar. The Spanish spirit which Santamania contributed is based on Spanish Tempranillo. It was made in sadly limited quantities. Each distillery contributed gin which was blended. The result is terrific. I suspect it sold out ages ago.

It is clean, zesty and flavoursome with juniper notes supported by florals and citrus/lime touches. A hint spicy and a lovely creamy and supple texture. Good gin!

The cigar was the Trinidad Coloniales, a corona of 132 mm in length and a ring gauge of 44 mm. While I am not sure I have ever met a Trinny I didn’t like, also not certain that this is my favourite. Well, actually, I am certain it is not. Fundies, La Trova and a few others would elbow it well out of consideration.

All that said, it was perfectly pleasant. Roasted nuts and campfire notes to kick off. It had that really appealing smell that takes one to sitting around a campfire on a winter’s night. It was quite powerful and rather smoky (yes, that sounds really odd and what else would it be, but you know what I mean. And if you don’t, humble apologies). Quite woody. There was also some caramel trying to emerge throughout. After a bit, it settled into a richly flavoured cigar. Balanced but definitely powerful. I was really enjoying it and I was sitting around 93-94, until we hit the last third.

All a bit bizarre. It was going so well and then the thing just collapsed and badly so. The construction had been perfect. There was no hint of a problem. Then it all unravelled. Literally and figuratively. All a bit like that date that seems to be going well and then suddenly craters before your eyes and you have absolutely no idea why. Normally, I have an idea why, but not this time. The lovely flavours I had been enjoying and were replaced by unpleasant, dirty characters. So unfortunate. I don’t think I have ever seen a cigar collapse so quickly. If you average it all out, 88. But that seems unsatisfactory. It was either much better or much worse.

The gin worked very nicely for the first part. Nothing would have saved the second bit.

So, this seems an ideal time to pinch from a recent piece I did on gin for Quill and Pad (https://quillandpad.com/2020/08/11/gincredible-how-and-why-gin-went-from-murderous-swill-to-007-level-cool/).

I remember in the days before the internet, laptops and mobile phones (yes, that old), just how different things used to be. And better, of course.

Travelling. These days, you can find anyone, anywhere. How boring is that. When I left London around ’87, after a couple of years studying/working (yes, that old), I spent almost all the next year just travelling. Africa, Asia and then ended up in DC to join a local law firm. For at least six months, no one I knew had any idea which hemisphere I was in, let alone continent or town. I quite liked that. I wrote letters home but in Africa, reverse charge calls were not permitted (they wanted the income) and calls to Australia were horrendously expensive. Monthly salary expensive.

Travellers got their updates from talking to others doing the same thing, although usually going in the opposite direction, not from daily emails and apps and influencers (has there ever been a more useless occupation?).

So travelling up through Syria back then, remembering that the Middle East was enjoying as many problems and wars as ever, one had to take a little care, although perhaps things might be a smidge worse these days. I remember Aleppo as a fabulous city where I had a heap of fun. I really doubt many would echo that, these days.

Word was that, when in Damascus, if one went down a certain back alley between 2 and 3pm, and knocked on the yellow wooden trapdoor, one could buy alcohol. Presumably, you could also do so in five-star hotels but we were not quite sartorially appropriate for such establishments, after months in the back of a truck through desert and jungle.

2pm came and the window opened. Behind the vendor, several shelves offering Syrian Vodka, Syrian Whisky, Syrian Brandy, Syrian Rum and Syrian Gin. They all looked identical. Clear spirit in cheap bottles.

I went gin. At least it looked like gin. The following day reigns supreme as the worst hangover I have ever had. Unimaginable. To this day, I give thanks I survived. I honestly believed that if I tried this today, I would be very unlikely to survive. Others did not fare quite so badly, though they might not have sampled their product quite so extensively. I can promise that the remains in my bottle, a fair whack, went down a Syrian drain.

Gin has copped a bad wrap at various times in its history. As the old song says, “The gin like a demon was howling.”

Hogarth’s excruciating Gin Lane paintings from the 1750s are evidence that there were times when gin was little better than my Syrian swill. The gin craze du jour seems to have been at its peak between 1695 and the 1740s. Its popularity had exploded thanks to heavy taxation of French brandy. More than 8,000 gin shops sprang up in the UK (some 7,000 in London alone), along with 1,500 residential stills and who knows how many illegal operations. Cheap alcohol for the poor. Turpentine was often added and the use of sulphuric acid was not unknown. A typical sign outside a gin shop was “Drunk for a penny. Dead drunk for twopence. Clean straw for nothing.”

In 1734, it is estimated that some 5,000,000 gallons of gin were consumed. By 1742, this had risen to over 7,000,000 gallons, an annual consumption of gin per person in England of 10 litres. Cheap gin was often used to pay wages. Around this time, there were twice the burials as baptisms. This period also saw an enterprising soul invent what is believed to be the first vending machine. In the form of a giant cat, needless to say, it provided the customers with gin (money in the mouth, gin from a tube under the paw).

An emotionless description by a woman of murdering a child so she could steal the child’s coat to sell, in order to buy gin, is one of the most chilling things imaginable. The woman was hanged, unsurprisingly. It was her own daughter whom she murdered.

There were eight different Gin Acts between 1729 and 1751, designed to stop the rot. The Gin Act of 1751 was the most successful, though historian Peter Ackroyd, thinks the Act had nothing to do with the reduction in the consumption of gin. He puts it down to poor harvests rendering gin more expensive, the growing rise of Methodism and the increasing interest in tea.

Some years ago, gin was all rather English – Colonel Blimp, handlebar moustaches and pith helmets. A pink gin (whatever that was) at sunset, gin and tonics before dinner.

A friend was a fan. Gordons or Gilbeys. I remember how thrilled he was when he discovered something so exotic as Tanqueray’s famous green bottle. I doubt the divinities could have coped with the excitement had he stumbled across Hendriks back then, with its delicious cucumber/rose petal notes, let alone any of the endless array of weird and wonderful gins which feature some amazing botanicals and more. This was a time when gin was about as cool as watching the footy in a dressing gown and your beanie. Today, gin is 007-cool. Why? And when?

Famed bartender at the Savoy, Federico, believes that the creation of top quality tonic around 2004 was the catalyst. Suddenly, the G&T went upmarket. And if you have a top-notch tonic then you sure as hell had better have quality gin.

Today, gin really has exploded. It is made everywhere in every way and at every price point. A few years ago, I remember a report claiming that the UK now had more than 500 different gins. I thought it must be a misprint or at least an exaggeration. Now, we have more than 500 in Australia and more hit the market every day. Do we really need 500 plus gins? How many will be with us in five years? Ten?

Craft distilleries are behind much of this. I remain convinced that many of these places had grand dreams of producing a great whisky or rum, but discovered that they would not be offering a product for many years, given the time needed for maturation. Gin, on the other hand, is distillery to dollars in weeks (the name ‘bathtub gin’ was not for nothing). I suspect that many of these places have barrels of that dream whisky/rum maturing away in a dark corner and we’ll see these in time.

One originally thought of gin as a distilled spirit deriving its flavours largely from the juniper berry, although the juniper berry is not actually a berry but rather a cone of sorts (like pine cones) the enmeshed scales give the impression of a berry.

Today, gin includes ingredients that seem almost inconceivable. Originally made by monks in Italy, according to certain authorities, monks across Europe soon jumped on the juniper wagon (that said, like all these things, origins are shrouded in the mists of time and plenty will put up their hand to claim them). It was especially popular in the Netherlands (Dutch Courage, anyone?), where, known as jenever (later geneva/genever), it was once seen as a medicine. Before long, it spread to the UK. These days, it is popular everywhere but one unlikely country is responsible for around half the world consumption, if certain stats are to be believed – the Philippines!

Pot still gins ruled in the earlier days. When used these days, the result is usually aged in tanks or barrels to ensure the richer, heavier flavours are retained. After the invention of the Coffey Still, column distilled gins emerged. The result is usually a lighter style but it does allow the infusion of the various botanicals so essential today. Where the neutral spirit has been flavoured by infusion without further distillation, these gins are called compound gins.

The popularity of the good old G&T can be attributed to the inexorable expansion of the British Empire (visitors to Spain are often surprised to find that G&Ts popularity is even more pronounced there, though friends in Madrid tell me that this was because of RAF officers stationed in Spain at various times – no idea if this is true).

Some of the British conquests proved home to a few too many mosquitos and malaria was a genuine danger. Quinine was the most effective defence at the time, but it was unpleasantly bitter. Hence, quinine was dissolved in carbonated water, becoming tonic water. Today’s tonic includes far less quinine but then no one is taking it to avoid malaria. Gin was then added to the tonic to help mask the bitterness.

As Sir Winston Churchill said, “The gin and tonic has saved more Englishmen’s lives, and minds, than all the doctors in the Empire.”

Variations emerged. Sloe gin was basically a liqueur made from soaking the fruit of the blackthorn tree in gin. Pimm’s No 1 Cup is another variation.

London gin is dry (less than 0.01g of sugar per litre of alcohol) and pure, and not necessarily from London. There are a couple of gins which must be made in a specific location – Mahón Gin from Menorca and Vilnius Gin from Lithuania – are examples. Plymouth Gin was considered as a “geographical” gin, but since 2014 (or 2015, depending on the source) has been classified as a London Dry Gin. The Black Friars Distillery is Plymouth’s only remaining distillery. Located in what was a Dominican monastery built in 1431, it has been distilling since the 1790s. It is now owned by Pernod Ricard.

No artificial flavourings or additives can be added after distillation in the making of a London Dry Gin. The ubiquitous blue bottle for Bombay Sapphire is a good example of this style.

Navy Strength Gin is gin bottled at 57% and below 58% ABV. Gins higher than 58% are simply called high strength gins.

Different countries will have varying minimum alcohol levels, permitted additions and regulations for exactly what can be called gin (one expects the inclusion of at least a token of juniper) but overall, the category is well known and broadly encompassing.

Old Tom gins are less popular than they once were. A sweeter style, thanks to the addition of sugar or honey, it was much loved during the 18th Century gin craze. No doubt, its origins were simply a way to camouflage the horrendous quality of the gin many of these establishments were pushing. It has largely morphed into a gin cocktail called Tom Collins.

Gin is an essential ingredient for many of the most famous cocktails, including the King of them all, the Martini (I do not care what 007 says, a Martini requires gin, not vodka – and yes, I am aware that others disagree, but I can’t help that and all the correspondence in the world will not change my mind). The Gimlet, Negroni and Singapore Sling are other legendary gin cocktails.

I mentioned I came from an era when gin was the epitome of the uncool. The exception was undoubtedly the Martini. Now, we can undoubtedly argue the percentages and methods for hours, olives and twists – could this possibly be where Dickens got Oliver Twist? Again, not up for discussion is that a Martini is made with gin, not vodka. What is also a certainty is at the time there was little as seemingly sophisticated as this basic, elegant cocktail. We were assured that the drier the better (the less vermouth, the drier your Martini). Luis Buñuel captured the imagination of us all when he dictated that one poured the gin into the glass and then held the bottle of vermouth up to allow a shaft of sunlight to shine through the bottle and on to the gin. Noel Coward matched that by insisting that “a perfect martini should be made by filling a glass with gin, then waving it in the general direction of Italy.”

Next time we look at gin, we might delve into some of the weird ones.

KBG